Australia’s migration numbers reveal more than just demographic change — they expose a deep shift in who gains access to the country’s best economic opportunities.

In the 2023–24 Migration Program, India received 49,848 permanent visa places — over a quarter of all new permanent spots and a 21 per cent increase from the year before. The number of Indian-born residents has grown to 916,000, a 3.7-fold rise since 2006. For context, 31.5 per cent of Australia’s total population is now overseas-born, the highest share in national history.

A workforce reshaped

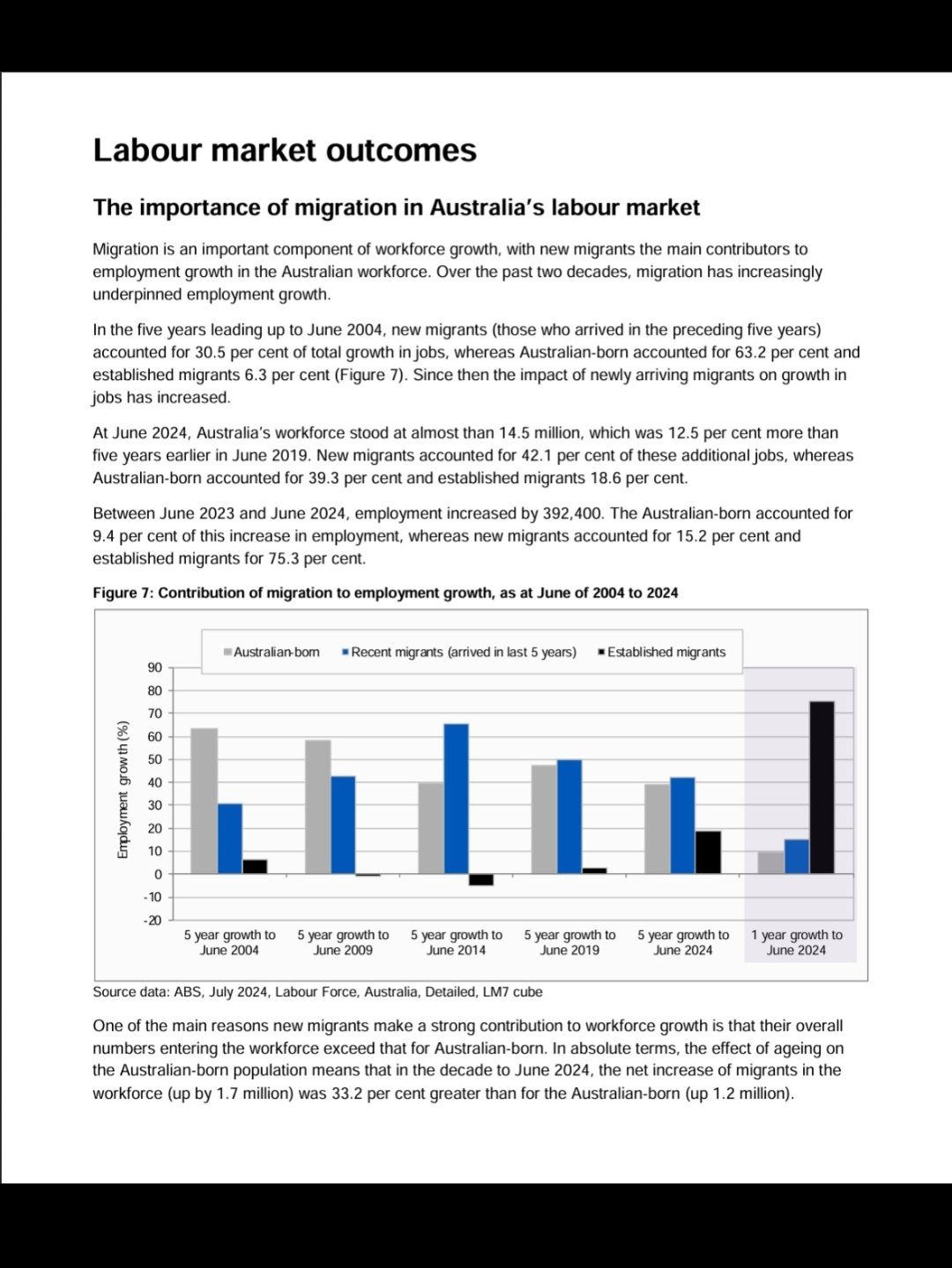

Most Indian migrants are young, highly qualified, and employed in high-income industries such as IT, engineering, medicine, and academia. They fill real skill shortages — but the consequence is structural displacement.

The ABS shows that 68 per cent of Indian arrivals since 2006 hold a degree or higher, and their labour-force participation rate exceeds 85 per cent. By comparison, many Australian-born workers — including European, Eastern European, East Asian, and other minority backgrounds — are slipping down the income ladder, increasingly confined to lower-skill or casualised work.

The policy imbalance

Instead of fixing education and training pipelines for local youth, Canberra leans on imported talent.

Universities are overloaded, TAFE systems underfunded, and wages in entry-level technical fields have stagnated. A generation of young Australians is priced out of housing, burdened by student debt, and told to “retrain” for jobs that never appear — while visa pathways expand for external recruitment.

This isn’t anti-migrant rhetoric. It’s a question of national capacity: why outsource long-term workforce development when domestic education could produce the same skills?

Skilled migration fills short-term gaps, but over-reliance on it depresses incentives to train citizens, fragments social cohesion, and tilts the labour market toward transnational hiring networks over merit-based domestic mobility.

Why the Albanese government leans toward India

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s alignment with India is driven by realpolitik — economic, diplomatic, and electoral:

1. Economic leverage – India is a high-growth market with English-speaking professionals who fit easily into Australia’s services economy. Bilateral trade agreements (ECTA, CECA) and labour-mobility pacts guarantee a steady inflow of skilled workers without political friction.

2. Strategic hedging – As relations with China remain tense, deepening ties with India strengthens Australia’s Indo-Pacific posture. Defence cooperation and migration policy now move in parallel.

3. Political optics – The Indian-Australian diaspora is affluent, expanding, and increasingly influential in key electorates. Building rapport with it carries little downside in a multicultural political environment.

Each motive makes rational sense on paper — but together they risk creating a dual economy: one tier imported and credentialed, the other domestic and underemployed.

A warning from realism

Realists deal in outcomes, not sentiment.

A nation that depends on external labour to sustain productivity while its own citizens fall behind is eroding sovereignty by degrees. Australia’s future strength depends on balancing openness with internal renewal — investing in the education, research, and productivity of the population already here, regardless of ancestry.

The issue is not ethnicity. It is structural dependency disguised as progress.

If migration policy continues to substitute for national development, the result will be a divided economy: globally integrated but domestically stagnant.

-kianlayer0